“Real Life”, by Lewis Shiner

It’s dinner time, but I can’t get my wife’s attention. She’s killing Ants. Not little black ones out in the garden, but six-foot high Ants with space ships and photon torpedoes. So I pop a cup of alphabet soup in the micro and sit down with the evening paper. Here’s President Quayle on the front page, shaking hands with John F. Kennedy.

What?

Dinner’s ready. I pour it into a bowl and the letters spin queasily. They’re forming words. The words say, EAT ULTRAVIOLET DEATH, TERRAN SCUM.

Days like this, you wonder what the hell ever happened to reality. My wife has her answer. For her it’s a glove studded with wires and sensors and a helmet with built-in goggles and headphones. For the Associated Press it’s digitized wire photos that they can change with a stroke of the light-pen. But that still doesn’t explain what’s going on in my soup.

Life here in the nineties is weird and getting weirder. Me, I like to seek solace in literature. Back in the eighties I used to be into William S. Burroughs. Wasn’t everybody? I mean, the guy was practically a pop star, with everybody from the Soft Machine to Steely Dan to Thin White Rope ripping their names off from his books. It was hip to be paranoid, random, ironic, perverse. To be literate and still get to toy with all that slightly tacky genre stuff–private eyes, heavy-metal addict aliens, pornographic sex. Not just hip, it was downright postmodern.

Burroughs’ vision started losing it when Bush went to war on drugs. It was no longer cool to enjoy being stoned or even to talk about it–especially if you wanted to keep your job. Reality was turning into serious business, government business, multinational business. Do not try this at home.

Then technology got away from the guys with pocket protectors and suddenly there was Computer Aided Design and digital audio and hand-held video-games. Reality changed. In fact reality was getting harder to pin down every day.

If the eighties were William S. Burroughs, then the nineties are Philip K. Dick.

You remember Phil Dick. He’s the guy they took Blade Runner and Total Recall from. Now all of sudden everybody is asking the same questions that Dick started asking back in the fifties, and kept on asking right up until he died. How do you tell robots from human beings? How do you know that’s really your memory, and not some construct that’s been planted in your head? Are we fighting a real war, or are we being manipulated by politicians and corporations to keep spending money–money that is itself just electromagnetic data?

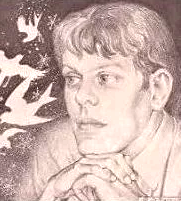

Only Dick was no William S. Burroughs-style rock star. He was overweight and dipped snuff and cruised mental wards for dates. Where Burroughs was a literary darling, Dick was stuck in the SF trash/pulp ghetto and never got out. He mixed up high and low culture, like Burroughs did, everything from Heraclitus to pulp sf to the Holy Bible, but for Dick there was no irony involved. If there was such a thing as the “information virus” that Burroughs talked about, Dick believed it was benign. He wanted answers for the weird shit in his life and he didn’t care where he got them.

Now everybody’s life is a little like that. There’s information everywhere and “high” and “low” doesn’t mean much anymore. The science fiction stuff from Dick’s books is now physically out there. And there’s more weird shit than most of us can handle. Those moments when the whole facade starts to break down and the word “reality” no longer means anything at all. Like that nasty moment when the helmet comes off and the “virtual” reality just goes away.

Okay, okay, we all know what reality really is. Reality is smog alerts, crowded freeways, famine in Africa, AIDS and drug wars and the homeless. Ozone holes and global warming and disappearing rain forests. But who wants to live in a world like that? When we can have infinite mental playgrounds that range from the geometries of Tron to the virgin planets and blazing space of Star Wars? After all, if we didn’t believe in the power of illusion, why would we have elected Reagan and Bush and now Quayle?

In books like Time Out Of Joint and The Three Stigmata Of Palmer Eldritch, Phil Dick told us, over and over, that Things Are Not What They Seem. He said that the measure of humanity is kindness–caritas–not the ability to look good on TV. He said that no matter how much you believe you’re in sunny Southern California, sooner or later you’re going to wake up to a lipstick scrawl on the bathroom mirror that says we’re all wasting away in an underground hovel on Mars.

It’s the same feeling you get when your air-conditioned, cellular-phone and CD-stereo equipped town car breaks down and you have to climb out into the heat of the ghetto. There’s another world out there, and it’s just dying to meet you face to face.

It’s the feeling you get when the power goes out in the middle of the Cosby Show. When that wino wanders into your restaurant and ruins your New American Cuisine. When a computer virus takes you down right in the middle of your spreadsheet. When you’ve been talking to a salesman on the telephone for two minutes before you realize it’s a computerized recording, or, here in the nineties, a full-fledged expert system that can bother a thousand people at once.

And in the time in between, when life seems to glide happily along, you may find yourself asking more and more questions. Is it live, or is it maybe Memorex after all? Is that Schwarzenegger blowing up pretend villains or is that news footage from El Salvador? Is Coke, in fact, the Real Thing?

And what is that in my soup?

The text above was retrieved from Shiner’s own website, where it was published under a creative commons license. Below you can read Robert Crumb’s comic book about Philip K. Dick from archive.org.

>