Along the southern fringe of the Sahara (the largest desert in the world) lies the Sahel, a sparsely vegetated transitional area between the desert and the savanna. In Arabic ‘sahel’ means ‘shore’, as if the Sahara were a sea of sand and rock, crossed by caravans of camels in the guise of ships, and the cities of the Sahel the ports where the camels offload their cargo. This open area runs from the mouth of the Senegal River on the Atlantic to the far reaches of Lake Chad without any major geographical obstacles. Despite being a semi-arid zone, the Sahel is wonderfully irrigated by the excellent Niger and Senegal river systems. Thus the Sahel is concomitantly home to agricultural communities (Wolof, Serer, Soninke, Malinke, Songhai and Hausa), pastoral communities (Berbers and Fulani) and fishing communities (Thioubalo, Sorko and Bozo). There were three great empires in succession in the Sahel, originally called Bilād al-Sudan by Berber Arab travellers and geographers, between the fourth and sixteenth centuries – the Ghana Empire, the Mali Empire and the Songhai Empire.

Islam in the Sahel

Islam made inroads into the Sahel in the second century of the Hegira. In 734, an Omayyad expedition crossed the Sahara into the ‘State of Ghana’, from which it brought back an abundance of gold; the area then became known as the ‘land of gold’, the Muslims’ genuine el Dorado. The military expedition was short-lived, but it paved the way for trade. It is noteworthy that Islam spread peacefully in Bilād al-Sudan, through the influence of merchants and holy men, not by force of arms.

Subsequent travellers and geographers underlined the splendour of Ghana’s sovereigns, who held sway over several Bilād al-Sudan kingdoms, including those of Mali and Songhai.

In the tenth century, the traveller and geographer Ibn Hawqal described the king of Ghana as ‘the richest sovereign on earth, for he possesses great wealth and reserves of gold that have been extracted since early times to the advantage of former kings and his own.’

News of the ‘land of gold’ actually triggered a rush by Muslim merchants, particularly as the very open-minded and tolerant animist princes and kings employed Muslims as advisers. The Andalusian geographer al-Bakrī wrote that the sovereign had a mosque built near his palace for Muslims visiting the royal city on business – a tolerant environment that contributed to the rapid spread of Islam among the various peoples.

The consequences of the discovery of the Sahel were considerable, for the Muslim world therefore extended well beyond the Sahara, encompassing a multitude of black peoples. With its abundance of gold, the Sahel, the new dominion won over to Islam, was literally an inexhaustible source of the precious metal that was then in desperately short supply in both the Muslim and the Christian West. The Sahel thus held pride of place in the concert of Muslim nations and kingdoms. Sahelian cities – Audaghost, Kumbi, Niani, Timbuktu and Gao – throve as staging posts on the caravan routes that linked them to international trade.

From the ninth to the thirteenth centuries, Sijilmasa, a caravan city in southern Morocco and bridgehead to the cities in the Sahel, was a meeting place for merchants not only from the Maghreb and Spain but also from the Mashriq, in particular Basra, Kufa and Baghdad. Merchants of the latter city, who had settled in large numbers in Sijilmasa, specialized in the gold trade with two major Sahelian cities – Kumbi and Audaghost. The traveller Ibn Hawqal wrote that ‘they won considerable profits, great advantages and ample wealth’ and that ‘very few traders in Islamic countries are as well established’.

As an example of the wealth of the Bilād al-Sudan merchants and the scale of their transactions, Ibn Hawqal reported an unprecedented incident: in the city of Audaghost, the second largest city in the Ghana Empire, he saw a merchant with a bill for 42,000 dinars made out to a merchant in Sijilmasa. He noted in amazement, ‘I have never seen or heard the like of this in the East. I have told the story in Iraq, in Fars and in Khorasan, and everyone has found it incredible.’

Sijilmasa reached the height of its glory in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Al-Mas˓ūdī, the author of Meadows of gold and mines of gems, wrote, ‘All of the gold used by merchants is struck at Sijilmasa, particularly dinars’.

Other mints were opened up later, in Almoravid times, mainly in Aghmat, Tlemcen and Marrakesh. The cities in the Sahel were very charming; travellers from the East were particularly impressed by Audaghost, for they thought that ‘of all the cities in the world, it resembles Mecca the most’.

Trans-Saharan trade boomed under the emperors of Mali, and Islam reached far south into the savannah to Sudan. However, when the trade routes shifted towards Egypt, Sijilmasa declined in importance and Kumbi was over shadowed by Niani, the capital of Mali.

The emperors of Mali effectively controlled imports and exports by means of a tax system that filled the public coffers, and the Songhai cities of Timbuktu and Gao gained greatly by the revival of trade in Mali. Converted to Islam in the eleventh century, the emperors of Mali were devout Muslims and several went on pilgrimage to Mecca. The most famous was Mansa Musa, whose 1324 pilgrimage was widely discussed in the Maghreb and Egypt until the very end of the century. Mansa Musa lived in grand style, with a retinue of some 10,000 people; he and his retinue completely flooded the Egyptian capital with so much gold that the value of the dinar plummeted. The lavish pilgrim gave alms generously in the holy cities and brought back to Mali several men of learning, sharīfs and an architect, Isḥāq al-Tuedjin, who built him in Timbuktu a palace (madugu) and the great mosque (djinguereber). He built another mosque in Gao and is credited with the Goundam and Diré mosques. He also built a mosque and an audience chamber for the sovereign in Niani. The emperor’s architect settled in Timbuktu, where he died in 1346.

That pilgrimage had far-reaching consequences, both in the Muslim world and the Christian west. The myth or legend of Bilād al-Sudan extraordinarily rich in gold was one that came true; Christians learnt of the pilgrimage from Muslim accounts, and Europeans became genuinely interested in the region. Thus, Angelino Dulcert’s famous map revealed to Christians in 1339 the existence of a gold-rich ‘Rex Melli’ and, in 1375, the Majorcans, who had gleaned this knowledge from the Arabs, produced a very accurate map of Africa showing Mansa Musa on a throne holding a nugget of gold. From the fourteenth century onwards many attempts were made by Europeans to fathom the secret of the trans-Saharan routes leading to ‘Rex Melli’. The best-known European exploration was the journey in 1447 by Malfante, a Genoan, as far as Tuat, but he could not go any farther. Europe’s ‘gold lust’ grew stronger; ‘Sudanese gold’ fever inflamed minds, but the ‘Muslim curtain’ remained impassable. Minting resumed in Europe in the fourteenth century, however, when Bilād al-Sudan gold was supplied by the Muslims.

After the emperors of Mali, the sovereigns of Songhai, fully aware of the stakes and wishing to maximize profits from the trans-Saharan trade, tightened control over imports and exports. The Egyptians, for their part, very effectively prohibited all Christian inroads south of Cairo.

Under the Songhai emperors, Islam in the Bilād al-Sudan spread beyond city confines to the countryside owing to the influence of black Wangara, Soninke and Songhai merchants. The Songhai emperors were not only devout Muslims but also, for the most part, fine men of letters. Askiya Muhammad made the pilgrimage to Mecca accompanied by many learned men and Qur˒ānic scholars. Upon his return, after being dubbed Caliph of Takrur (West Africa) by Moulay El-Abbas, the Ḥassanid sharīf, imam of Mecca, Askiya Muhammad began to spread Islam through jihād. Anxious to rule in accordance with Qur˒ānic precepts, he consulted celebrated figures such as al-Suyūṭī, the Arab writer, and al-Maghili, the famous Tlemcen legal scholar. Being an enlightened sovereign, he encouraged the advancement of learning by granting stipends to Islamic scholars.

As a result, the Sahel became an integral part of the Muslim world during the reign of the Songhai emperors. Sovereigns of the Sahel and sovereigns of the Maghreb and Egypt exchanged letters and gifts.

One sign of such integration was the frequency of missions and journeys from Bilād al-Sudan to the cities of the Maghreb and Egypt. Cairo was home to many merchants and scholars from Bilād al-Sudan. In the late fourteenth century, the great historian Ibn Khaldūn obtained first-hand information about the sovereigns of Mali from that country’s embassy in Cairo. The very existence of many principalities and cities in the Maghreb was closely linked to improved relations with the Sahel. Thus Muslims could trade and travel in a vast area from the shores of the Mediterranean across the Sahara to the Niger Bend. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Cairo became a hub for pilgrims from cities throughout the Sahel; many sovereigns, including Mansa Musa and Askiya Muhammad, bought houses in holy cities to accommodate pilgrims from Bilād al-Sudan.

It is noteworthy that geographical knowledge in the Muslim world was much greater than the information provided by Ptolemy in ancient times, which was still being used in its original form in the Christian West.

The age of the Askiyas

Songhai humanism It is not easy to pinpoint the apogee of a civilization. Did the Bilād al-Sudan civilization and Islam in the Sahel reach their zenith in the tenth and eleventh centuries when the Ghana Empire, the ‘land of gold’, drew merchants not only from the Maghreb but also from Khorasan, Baghdad and Basra and when bills and other letters of credit were circulating between Audaghost and Sijilmasa, or in the fourteenth century when the Mali emperor Mansa Musa and his numerous suite of pilgrims flooded Cairo and the holy cities with gold, or in the age of the Songhai emperors, when Askiya Muhammad returned from Mecca with his retinue of learned men and Islamic scholars, crowned with the title of Caliph of West Africa?

Those periods were all high points, but the age of the Askiyas was particularly outstanding owing to the brilliance of its intellectual works and the humanism that blossomed along the Niger Bend. The Songhai Empire provided the background for a dazzling black Muslim civilization, to which the Songhai, Soninke, Mandingo, Berbers and Fulani all contributed. At the time Gao, Timbuktu and Jenne were cosmopolitan cities in which all ethnic groups of the Sahel mingled. There were many Arabs and Berbers as well. Islam was a powerful unifying force in the Sahel both spiritually and culturally; in those cities where trade brought together people of different ethnic origins, their shared faith created a convivial atmosphere conducive to fruitful commingling.

Art

The art of the Sahel, commonly known as ‘Sudanese art’, is merely the outcome of techniques and practises that blossomed and peaked under the Ghana and Mali empires. Mansa Musa, both a patron and a builder, owing to the work of his architect Isḥāq al-Tuedjin, set his stamp on Sudanese architecture: adobe edifices reinforced by projecting wooden stakes. The monuments in Jenne, Timbuktu and Gao are particularly typical of this style.

This architecture reached its peak in the sixteenth century in the age of the Askiyas, who were great builders. Most of the buildings that are the pride of present-day Timbuktu and Gao date from the age of the Askiyas; the Sahel’s semi-arid climate has preserved these adobe monuments well. The craftsmen and masons of Jenne, the master builders of those imposing monuments, formed a powerful guild in the service of the sovereigns. The great mosque of Timbuktu (Djinguereber mosque) built by Mansa Musa was completely restored by Askiya Dawud, son of Askiya Muhammad, and the famous qāḍī al-Aqib; with its timber spikes and the flattened cone of its minaret, it dominates the entire city. The same qāḍī built the Sankore mosque, and its simple and austere lines won travellers’ admiration. It is now the seat of the University of Timbuktu.

In Gao the pyramidal tomb of Askiya Muhammad genuinely epitomised the Sudanese style, with its majestic bulk exuding grace and nobility. The monument that really symbolized elegance, however, was the mosque of Jenne, dating from the fourteenth century. Many residences of Islamic scholars and other men of letters in Timbuktu such as the house of Bagayogo and that of Abu-l-Barakāt, date back to that period. Civil architecture is well preserved in the Sahel on account of the dry climate.

Songhai humanism was religious in essence; ‘rather than being a revival’, wrote the historian Sekene Mody Cissoko, ‘it represented a flowering of African civilization, the outcome of a long history dating back to the Ghana Empire.’

Under the Askiyas the cities of Gao, Jenne and especially Timbuktu became both centres of intellectual life and seats of academic learning, drawing students from cities throughout the Sahel.

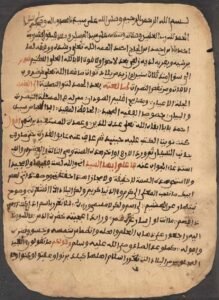

Study of the Qur˒ān formed the basis of education, since Arabic was the language of scholars and men of letters. Elementary education, provided by holy men throughout the city, was based on recitation and translation of the Qur˒ān. There were no fewer than 120 schools in the city of Timbuktu alone. Secondary education concentrated on interpretation of the Qur˒ān, while law (fikh), theology (tawḥīd), traditions (ḥadīth) and astronomy were taught at the university. Geography and history were held in high esteem in the Sahel,

Philosophy, law and letters

The sixteenth century was renowned for its scintillating intellectual activity, but the age of the Askiyas was above all that of the jurists, many of whom were famous, for Mohammed Touré, Salih Diawara, Mohammed Bagayogo, al-Aqib and Ahmed Baba all enjoyed the protection and liberality of the sovereigns. Several of them held the office of qāḍī in Jenne, Timbuktu or Gao, and all were theologians of great scholarship who devoted themselves to religious disciplines. However, few were drawn to the positive sciences; the heyday of Arab science admittedly lay in the past, in the fourteenth century. Although their works cannot all be mentioned, a few words will be said about two of the most celebrated scholars of the age of the Askiyas – Mohammed Bagayogo and Ahmed Baba.

Mohammed Bagayogo was a great jurist, a thinker and an outstanding teacher; the Timbuktu historian ˓Abderrahman Sadi wrote of Mohammed Bagayogo that with his ‘fine, scrupulous and lively wit and shrewd, discerning mind, always ready with a reply and with the quick understanding of a brilliant intellect, he was a man of few words.’ This peerless teacher had a large library that was open to anyone in search of knowledge. He was also a theologian and grammarian, and his lectures at Sankore were well-attended.

The great sixteenth-century scholar Sidi Ahmed Baba (1556–1627) was a pupil of Mohammed Bagayogo. Born in Arawan into a family of scholars, he was ‘the jewel of his age’ and ‘his vast intellect and his infallible memory made him a mine of knowledge’.

He was a historian, a theologian and a jurist. When taken to Marrakesh as a prisoner, as were many scholars from Timbuktu after the Sultan of Morocco had captured the city, he impressed the scholars there. The Sultan freed him and gave him permission to teach. The Arab men of learning called him the ‘standard of standards’. He had one of the largest libraries in the city, thought to contain more than 1,700 works. He wrote a substantial amount, but only extracts from two of his works have survived – Nayl al-ibtihāj, a bibliographical encyclopaedia of Islamic scholars and other learned men, and Mi ˓rāj al-ṣu ˓ūd, devoted to the history of the peoples of Bilād al-Sudan.

History flourished in the age of the Askiyas: a family of historians – Maḥmud Kati (1468–1554) and his grandson – produced Tārīkh al-fattāsh, a work dedicated to the history of the Askiyas, which contains valuable information about the Sahelian kingdoms.

˓Abderrahman Sadi was the great historian of the Sahel: his Tārīkh al-Sudān covers the entire history of the Songhai Empire, and his critical judgment is outstanding.

Animated map from youtube

Timbuktu, the great Songhai metropolis, had 100,000 inhabitants in the late sixteenth century; its influence extended throughout the Sahel, drawing thousands of students, doctors, jurists and teachers of renown. The city had attained a high degree of sophistication. To quote the historian Kati, who described it shortly before it was captured by Spanish mercenary converts in 1591, ‘Timbuktu had reached the pinnacle of beauty and splendour; religion flourished within its confines, and the Sunna inspired every aspect of not only religious but also worldly affairs, although these two fields are apparently incompatible by definition. At the time Timbuktu was unrivalled among the cities of Bilād al-Sudan from Mali to the outer fringes of the Maghreb for the soundness of its institutions, its political freedoms, the purity of its morals, the safety of people and property, its clemency and compassion towards the poor and strangers, its courtesy to students and men of science and the assistance provided to the latter.’

Timbuktu was also a city of saints, whose tombs were visited by large numbers of people wanting to make a wish. It was the city of the San, the scholars who lived around the Sankore mosque (Sankore being the scholars’ quarter). Under the Askiyas, the city was placed under the authority of the qāḍī, who acted as mayor. He was responsible for managing taxation in the city and for providing all public services.

The qāḍīs of Timbuktu, who were respected by the Askiyas, governed the city very fairly; the inhabitants were peaceful people who dreaded violence: ‘You could come across a hundred of them, and none would have a lance, a sabre, a knife or anything but a staff ’ (Mahmud Kati).

The capture of Timbuktu by Moroccan troops was a disaster, but the deportation of the Islamic scholars to Morocco in 1593 was, to quote the historian Kati, ‘the greatest injury ever done to Islam’.

Without those illustrious figures, the city became a shell with no soul. It was a step backwards for civilization, and Timbuktu took a long time to recover.

This article was published online at the UNESCO website under a creative commons license: CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO